The Time I Joined Peace Corps and Worked With An African HIV Program for Sex Workers in eSwatini: Part 1

Once upon a time, I joined the Peace Corps

I served in the United States Peace Corps in my early twenties. I barely wrote about it at the time.1

In part, I wrote little about it because it was an incredibly difficult experience, hard to process. I felt a lot of despair. Also, the Peace Corps discourages Volunteers from posting on social media, or at least they did when I was in the program.

But, most importantly: I think Peace Corps is unique and incredibly valuable. My service showed me some wild things about humanity and about the international establishment. Many of those things were bad, but I think it was good that I saw them.

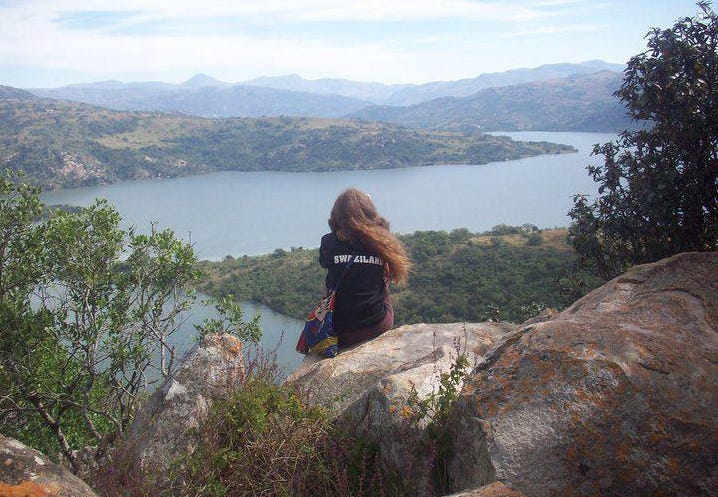

At the time, I did not believe writing about my experience would help development professionals on the ground, trying to make a difference. Also, I didn’t want to get any of the Africans I met in eSwatini (formerly known as Swaziland2) in trouble; it did not strike me that the situation was their fault.

So, on the day I returned to the USA, I told myself I wouldn’t publish my Peace Corps story for at least ten years.

That was in 2010.

—

—

I began writing this post before the current political situation erupted. But right now, I am adding this section because the incoming presidential administration appears intent on defunding many US international aid programs.

As I get close to hitting the publish button, this is the context. So I want to be absolutely clear about this. I believe the actions of the current administration are likely to cause a lot of harm. But that is not because what was happening previously was functional. It wasn’t.

It can cause enormous harm to suddenly destroy a gigantic system people are depending on, even if the system is messed up. So I really hope the incoming administration is somehow persuaded to slow their roll.

—

I left in 2009 and returned in 2010.

I asked Peace Corps to send me anywhere but Africa. Southeast Asia was my top choice. Back then, it seemed important to Peace Corps recruiters that people not ask for this. So it was made clear to me that a location preference was a black mark, that it counted against me.3 “This isn’t a vacation,” one PC employee said to me, with faint but obvious contempt. Anyway, they sent me to Africa.

Often, as a teenager, I had daydreamed about Peace Corps. I didn’t apply right out of college, though. First I graduated and got my B.A. in 2004, when I was 19. Soon after I graduated, I moved to Chicago, and I started working in a local bookstore while writing on the side. I scored a cool internship with my favorite game design company, White Wolf Game Studio. Then I wrote games for a while. Eventually, however, I concluded that game design was not my path. So I was in my early twenties when I finally applied to Peace Corps.

Some people apply to Peace Corps and leave within months. My application process took two years, which is unusually long. The main reason it took so long was that, years earlier, when I was a teenager, I was institutionalized for suicidal tendencies. There was a question on the Peace Corps application that asked if I’d ever been institutionalized. When I answered that question, I told the truth. I was then required to undergo a full mental health evaluation to determine whether I possessed the emotional capacity to serve in Peace Corps, which I passed.

While applying, I asked Peace Corps about the percentage of Volunteers that quit. (The official PC term for voluntary quitting is Early Termination.) An employee told me that the highest rate of Early Termination he’d seen was 50%. The program with the 50% ET rate, he said, was in deep Mongolia, where many Volunteers had to stay inside with their host families for the entirety of winter, not leaving their homesteads, while external temperatures plunged far below zero. The employee then explained that the median ET rate, under normal Peace Corps circumstances, was closer to 30%. So, this was a huge part of what they selected for, he told me — a person’s projected capacity to stay through the whole program.4

My lengthy application process meant that my circumstances changed unexpectedly between the time I started applying and when I left. In the two years between application and departure, I became involved in the BDSM community. I created an online pseudonym, Clarisse Thorn. Writing as Clarisse, I rapidly became semi-famous for my commentary on BDSM, sexuality, and feminism. I did not expect this to happen and neither did anyone else I knew at the time. Blogging and social media were weird back then, niche interests, so I originally thought of Clarisse Thorn as a side project.

Even after I started getting famous, it was not obvious that internet fame was useful. The word “influencer” was not a word yet. But clearly I was good at… something. Really good at it. I started getting cool opportunities around Chicago, like curating a film series about sexuality and feminism at Jane Addams Hull-House Museum; my film series immediately became one of the museum’s most successful programs. My life felt like a rocket ship. I hardly slept for all the awesome, exciting, fulfilling stuff I got to do. And then, in mid-2009, I got the call.

Peace Corps had a post for me in eSwatini, Africa. Could I leave in a month? If I didn’t accept, they told me, then I might never get another offer.

So I went.

—

ESwatini is relatively small, geographically, about the size of New Jersey. When I was there, the population was about one million. It is one of the only absolute monarchies in the world, and the last absolute monarchy in Africa. The current king is King Mswati III. He was also king when I was there.

Within eSwatini, the king’s word is law. He is both the spiritual head of the country and its lawful leader. Some kings of eSwatini have reportedly done great work in this role. For example, colonialism happened emotionally across much of eSwatini, but it did not happen by force, because the nation was never militarily conquered. When I was there, I heard that eSwatini is an independent kingdom largely due to the brilliant diplomacy of the previous king, Mswati’s father Sobhuza.

One result of this situation is that there are two simultaneous intertwined systems of government: The old traditional Swazi government, and the new democratic government. In the old system, the king rules a loose band of councils, all of which are deeply integrated with the traditional religion. The new system feels more Western and Christian, and the new system contains elected democratic officials. But, because the king is the absolute ruler, the king has the official ability to overrule Parliament. So in that way, the new system is subordinate to the old system.

These two systems collide often, blatantly and subtly, but eSwatini is peaceful, especially compared to its neighbor South Africa. I once walked across the border between eSwatini and South Africa, and within a hundred feet, I felt the difference in how people watched me. Over the border in South Africa, as a white girl, I felt frightened and unwelcome in a way that I felt far less in eSwatini.

As soon as we arrived, it was instantly obvious to us Peace Corps Volunteers that there were many reasons to critique the Swazi monarchy. However, it was also made clear to us that this was not our job. We were expected, at all times, to respect Swazi culture and the ruling political structure. It was repeatedly explained to us that we were there at the invitation of the royal family. We were their honored guests, and it would harm Peace Corps if we gave any external indication of questioning the system, and that was the end of it.5

Peace Corps runs different programs in different countries. In 2009, the only PC program in eSwatini focused on HIV/AIDS. ESwatini, then and now, has the highest HIV rate in the world. When I was there, 25% of the general population and 40% of pregnant women had HIV.

This numeric percentage of living Swazi citizens did not reflect the many people who had already passed away from the disease. Of the dead, many would have been middle-aged in 2009, but instead they were gone, leaving orphaned children and devastated communities behind.

It was a remarkable coincidence that I happened to get placed in the Swazi HIV program; when I was accepted into Peace Corps eSwatini, they didn’t know that I had some expertise in sexuality, because all my sex writing was under a pseudonym. So the work I did in eSwatini was related to work I had already been doing, but they didn’t know that when they sent me there. For example, as part of my sex-positive activism in the USA, I had already learned quite a bit about sexually transmitted infections (obviously, this was partially because I was careful to protect myself from infection). Also, I’d read archival materials and had watched documentaries about how HIV affected American gay communities in the 1980s. And I knew a lot about monogamy and non-monogamy due to the subcultures where I spent my time. But, of course, eSwatini was very different from what I was used to. For one thing, I was accustomed to an environment where women had more rights.

One rumor we all heard, but were told not to spread, was that the king himself had HIV. This was plausible, as he had many wives, and there was no reason to believe that he restricted himself to his wives (he is not a man known for restraining his appetites). Indeed, it was generally normal for high-status Swazi men to have multiple wives, especially in the rural areas. Simultaneously, eSwatini, which was a fairly developed country, contained many educated women, including plenty of women working in jobs like men. Some of these educated Swazi women complained privately about the local gender norms.

At times it was hard to square our responsibility to respect Swazi culture with our role helping with HIV, because HIV, like all sexually transmitted infections, is intimately intertwined with cultural notions of gender and sexuality.6 Sometimes it was also difficult to understand our own personal boundaries. I remember seeing how another Volunteer struggled because she was so upset by the dress code we were told to follow. She wanted to be able to wear jeans. For whatever reason, this felt important to her. But tight pants were widely considered unacceptably slutty by our hosts. As women, we were told to wear long skirts and dresses, especially in the rural areas where most of us spent most of our time. The first Early Termination in our group occurred when she quit because of all the sexual harassment.

I remember a local situation widely reported in the Swazi newspapers. A Swazi husband had murdered his wife. He explained that he killed her because she wouldn’t have sex with him. It transpired that she had refused to have sex with him after he was diagnosed with HIV; she was tested too, and she didn’t have HIV. So she refused to have sex with him unless he used a condom, because she didn’t want to catch HIV.7 And so he murdered her.

This became a matter of national conversation: Was the man justified in killing his wife? Did she have the right to refuse sex to her husband at all, even if he had HIV and refused to use a condom?

Swazi feminists obviously said she had the right to refuse him. They deplored her death, as did commentators from NGOs working to contain HIV. But a lot of Swazis said no, she had no right to refuse him.

If I recall correctly, the local newspaper did a bunch of “man on the street” interviews, and quoted one person saying: “What did she expect?”

There’s another, darker example I can give. Sex by adults with very young people was common. I remember another story from the papers, this one about a fourteen-year-old girl who had the misfortune of catching the king’s eye without returning the king’s interest. The story, as reported by the paper, was that the girl’s family tried to get her out of the country to London, and allegedly, the king sent the Swazi secret service to get her back.8

Nobody had the slightest idea what to do about the prevalence of older people having sex with very young people. (Nobody, in any culture, ever knows what to do about this, as far as I can tell.) But it was an HIV vector, so there was HIV money available. So at one point, a local HIV-related NGO purchased a billboard over the largest public transit hub in eSwatini, which said:

“Are you thinking of raping a child today? Think twice of the consequences.”9

I saw that billboard dozens, maybe hundreds of times during my time in eSwatini. It faded into the background after a while.

These examples highlight a problem that was already clear to the HIV establishment well before I got there: In high-prevalence areas, HIV is not being transmitted because people don’t know about it or don’t know how to prevent it. It’s transmitted because the local norms make it hard — psychologically, logistically — for people to protect themselves.

It was once true that many Swazis didn’t know HIV was sexually transmitted, just as many gay Americans didn’t know in the 1980s. So, years before I got to eSwatini, people did catch the disease because they didn’t have accurate information about how it spread. But by the time my group served in Peace Corps, any Swazi schoolchild was capable of reciting the ABCs of HIV prevention: Abstain, Be faithful, or use Condoms.10

There are numerous reasons HIV spreads faster among some groups than others, but a lot of the time, at least in our era, it simply isn’t about whether they know the technical details of how to avoid it. (The same is true for other pandemics, by the way.)

Given that our job was preventing transmission of a disease that was completely intertwined with sex and gender, which is completely intertwined with power structures, what did it mean for Peace Corps Volunteers to stay uninvolved in power structures? On the surface, our neutrality was a simple matter, but underneath, many of us struggled with it constantly. There was also guilt to contend with. We all felt guilty, all the time, as we saw how unfathomably privileged we were, compared to the people we hoped to help. From what I understand, these are both common experiences among PCVs across programs, and these are core aspects of why the program is so hard.11

Peace Corps staff responded to our confusion and despair by emphasizing that the program had three goals:

1. Learn about other countries,

2. Teach other countries about America and Americans,

3. Help where needed.

On days that we felt like we weren’t accomplishing anything, or didn’t know what to do, then we were told to remind ourselves about the first and second goals.

—

Within the assigned country, Peace Corps Volunteers are usually tight-knit. After training, Volunteers are assigned to sites alone (married couples can serve together), but the initial training happens as a group, and often PCVs rely on each other for emotional support throughout service.

In short, we needed each other and we all knew it; keeping secrets from other PCVs would have been hard. So, during training, I did not try to hide my previous sex-positive activism or my sexual history from the other Volunteers. (Perhaps ironically, throughout my Peace Corps service I dated another Volunteer who had a religious vow of chastity, which I fully respected, which everyone thought was hilarious, but that’s a story for another time.)

As part of my immersion in the world of sex blogs, I’d read tons of writing by sex workers and their advocates, even though I wasn’t a sex worker myself. So I had a lot of feelings about protecting sex workers.12 I also cared about people in other sex subcultures, since I obviously was able to personally relate. But in Peace Corps, we were constantly told to be careful of our reputations. Associating ourselves with stigmatized minorities was verboten. So, we were told, hanging out with sex workers, even if we were trying to help them, would be frowned upon. Despite the fact that we were there to work on a stigmatized disease, we also knew that if we spent too much time with the “wrong kinds of people,” it would cause problems for us in the community and thereby make us less safe. The Peace Corps has a category called “High-Risk Behavior,” and if you do too much of it, you might get sent home; and it was clear that helping certain groups might count as High-Risk Behavior.

And yet! During our months of training, each Volunteer was evaluated and assigned to our individual sites. Mid-training, one of my fellow Volunteers heard about a new site, which was rumored to have an innovative program for sex workers. At one point, the program even sent a representative to Peace Corps HQ and pleaded to get one of us assigned to help them. So this was the one place in the entire country where the Volunteer had license to help local sex workers contend with HIV.

My friends and I plotted to get me assigned to the site, which was in Lavumisa, a town on the southern border. It worked. My friends got a picture of me screaming my head off with joy, in the moment I was assigned to Lavumisa.

—

Lavumisa was a small town, dusty with the red earth of eSwatini. It contained a border post, an old hotel, a small public transit hub for buses and vans, and a strip of several shops. Lavumisa was far more developed than the sites where my friends were posted; my one-room tin-roofed hut had electricity, which was an enormous luxury.

Many Peace Corps Volunteers learn quickly that few NGO workers venture into the areas they serve. When I was in eSwatini, we were some of the only Westerners anyone saw regularly out in the rural areas — us, and Doctors Without Borders.13 But this was not because there were few NGOs in eSwatini. On the contrary: Due to its immensely high HIV rate, eSwatini received one of the highest amounts of foreign aid per capita in the world (and last I checked, it still does). This meant that NGOs were, in their own way, one of the country’s dominant industries. Most NGOs in eSwatini had air-conditioned offices in Mbabane, the capital, or Manzini, the biggest city, and their employees pretty much stayed in those cities.

Some PC programs assign Volunteers to jobs, but others don’t. PC in eSwatini was in the second category: We were not assigned to a job; we were expected to figure out what might be helpful, and do it. After our initial months of training, we were sent to our sites, where we implemented the PC playbook for integrating into our communities, then filed Integration Reports with HQ, and then… somehow were supposed to make ourselves useful.

Like many of my peers, I set about the assignment with a will. I tried hard to meet everyone of note in the community, aside from the local traditional healer, who seemed never to be at home when I visited. (Many Swazi traditional healers prefer not to talk to white people.) In my long skirt and Chacos, I walked miles every day to see all the people I wanted to see.14

This is where I tell the story about the sex worker program. I can tell the tale succinctly because I’ve already told it, many times, in person over the years. Yet I find myself hesitating now.

I want to emphasize, again, that I do not believe this situation was anyone’s fault. Observing the program I’m about to describe made me really sad. But I’m glad Peace Corps sent me there. Part of why I didn’t tell this story for so long was that I worried about harming the Peace Corps and other people who are out there on the ground doing their best with what they’ve got. I have no desire to harm these programs, and yet telling this story feels right, now, for whatever reason.

In telling this story, it generally helps to start by explaining that foreign aid, like any industry, has its fashions. Those fashions are frequently disconnected from what would be most useful on the ground, i.e., the fashions are not set by the people the aid is ostensibly intended for, though there are some intersections. During the time I was in eSwatini, sex workers had recently become a popular target for aid dollars, i.e., a larger-than-usual subsection of the foreign aid Establishment decided sex workers are a high-value intervention point for HIV.

There was one pre-existing program in eSwatini that already served sex workers: A community group in Nhlangano, a village near Lavumisa. I heard that the Nhlangano program was originally created by sex workers, for sex workers, and that it was operational for years before the newly fashionable status of sex workers gained the program a bunch of cash, and hence, the ability to scale up. So they decided to do a spinoff program in Lavumisa. Someone, somewhere, had figured there had to be sex workers in Lavumisa — it was a border post, right, so there were probably sex workers, right? So someone, somewhere, allocated the money to set up a local office in Lavumisa, with several salaried employees. One of those employees was the man who came to Peace Corps and asked them to assign a Volunteer. I’ll call this gentleman Samkeliso (I have changed his name to a popular Swazi name).

Samkeliso welcomed me warmly and gave me access to everything I asked for. I attended meetings, chatted with the staff, and hung out with the women in the program. I learned that when they started the new program in Lavumisa, they had trouble finding local sex workers, so they identified one woman who they believed to be a sex worker, and they asked her to help them find other sex workers in order to create the new Lavumisa support group.

Financial incentives are common among NGO programs in the third world. In fact, the incentives are so popular that many people who collaborate with NGOs have come to expect financial incentives, even if they are not employees. Hence, it seemed natural to incentivize the first woman to bring other women into the program by paying her per woman she recruited.

When I learned this fact, I asked whether they had any way of checking on whether the other women in the program were, in actual fact, sex workers. Samkeliso acknowledged that they did not, in fact, have any way of checking on this. Therefore, they had begun referring to the program as a program for at-risk and marginalized women, rather than for sex workers.

Everyone who was recruited into the program expected plentiful incentives to participate in the program. So the program provided meals and getaways to nearby fancy hotels, for the group to bond and do community things. For a while, everyone involved was pleased by this. However, by the time I got there, there had commenced some broader pressure for the program to show concrete results.

What counted as concrete results? I will tell you now that I rarely saw an HIV-related NGO in eSwatini whose results were directly connected to the HIV rate. Now, I want to emphasize that to a large extent, this actually makes sense. In an environment like eSwatini in 2009, where a pandemic has run rampant and wrecked social structures, there’s a lot of work to be done, related to the pandemic, that does not necessarily connect to reducing HIV rates. So for example, you could imagine a situation where aid workers usefully teach in schools, replacing teachers killed by HIV, since so many middle-aged people were dead. You could also imagine a situation where people did childcare in order to help, since so many orphans had lost their parents to HIV.

In the case of the sex worker program, they chose to deliver the visible result of enabling the community group to start a business. It stood to reason, right — the sex workers were having sex for money, so giving them the opportunity to learn another line of work, while providing seed money for a new business, would surely help them escape the sex industry. Right?

I mean, it would have stood to reason if the sex worker group was in fact composed of sex workers. It wasn’t, but nobody seemed interested in discussing that fact, so I didn’t try to. I do recall a day when I briefly encountered the program’s main funder. He was white and, I think, had been raised in that area of the world, though I don’t recall exactly. I only saw him once. I guess I could have told him about my observations up to that point, but I was not at all sure what would happen if I tried, so I didn’t. I asked him what motivated him to donate to the program and he said that he wanted to help the women escape sex work due to his religious beliefs.

In fact, this was a phenomenon I’d already known about going in, because I’d already read so many sex worker blogs: Some activists call it the Rescue Mentality. When many people, especially religious funders, are trying to help sex workers, they often conclude that the way to help is to offer a path to escape sex work. One complicating factor is that many sex workers do not want to escape sex work, or in some cases, they don’t have any other options that are nearly as lucrative; and the “Rescue NGOs” cannot provide equally lucrative options, not without providing very extensive training in jobs that are a different kind of hard work. So a lot of people in the field already know that the Rescue Mentality is error-prone. But that doesn’t seem to affect its implementation rate, because there’s money for it, because people like to believe that they are rescuing sex workers from a life of sexual abuse. Nobody but weird activists seems to care about whether this model works as intended, and anyway, maybe sometimes it does work.

In this case, from what I could tell, the program did not work as advertised, but people very carefully weren’t paying attention to whether it did or not, because it brought money into the community. I assume the program also provided status and positive feelings to the funder. No one seemed motivated to audit the program in any serious way, so nobody did. My sense is that the majority of foreign aid programs are like this. That doesn’t mean nobody is doing good work, but it means that the ones who aren’t have little accountability.

In the end, this was how it went down: The NGO staff conducted some focus groups with the women in the “sex worker support group,” asking what sort of business the women wanted to start. (I think someone told me they also did a market analysis in Lavumisa. I never saw any evidence of this market analysis, but maybe it happened.) A list of bullet points was presented to the women, and I guess a majority of the women checked the box next to the “car wash” option, because a car wash was built.

This did not make sense, because the road running through Lavumisa was a dirt road colored with the vivid red earth of eSwatini. Therefore, any car washed at the Lavumisa car wash would soon need washing again. However, the same way I had not pointed out that the sex worker program was not composed of sex workers, and I had not pointed out that Rescue Mentality programs are known to fail at high rates, I also did not vocalize my concerns about the car wash as a sustainable business.

I later came to understand that speed was critical for this endeavor, because the NGO staff needed to publicly launch the project before sex workers stopped being such a popular target population for HIV interventions, because delivering a flashy and lauded program was what would propel them towards good future career opportunities. So the car wash was half-built when they hosted a ribbon-cutting ceremony. The staff got profiled in the papers alongside some politicians, providing quotable quotes about how proud they felt of this innovative program.

I lost track of them after that. Within months, they’d all gotten new jobs, at least one of which was among the air-conditioned NGO offices of Mbabane. The car wash remained an unfinished and half-built husk. Maybe someone eventually used it for something after I left Lavumisa.

When I think about my time working with that sex worker program, a particular scene comes to mind. I was visiting the local office in Lavumisa and chatting with Samkeliso. He took me into his office and closed the door. We talked for a while, him at his desk and me sitting in a chair across from him. Eventually Samkeliso said he had something to show me. He pulled a sheaf of papers from a filing cabinet and he handed it to me, but told me I could not take it out of the office.

The sheaf turned out to be a research report that the program had done with some actual, genuine local sex workers. As I sat in Samkeliso’s office and skimmed the report, I saw immediately that, once upon a time, his program had actually implemented all the actual, real, no-BS best practices for public health NGOs working within a community: They had humbly asked the women what they needed. And the women told them. As the report explained, sex workers in southern eSwatini wanted things like sex education, and they wanted help navigating difficult conversations about condom use, and so on.

In fact, much of the information in that report was in line with what I would have expected the women to want, and it was also in line with the sort of activities I would have expected to actually work to reduce HIV rates, based on the blogs I’d read by American sex workers, and based on the work I’d done at home with sex subcultures, and based on my Peace Corps training.

And all of it was completely un-fundable. The religious funder definitely wasn’t going to go for it, because then it wouldn’t be a rescue mission anymore. I couldn’t think of any relevant funding I could secure from American sources, either; funding from the United States is highly constrained due to a potpourri of political concerns.

I handed the sheaf of paper back to Samkeliso and looked out the window. As I recall, I didn’t say much. I don’t think he said much, either, after that. Today I wonder what he was thinking. In that moment, though, I felt like we had some deep shared understanding.

When I think of it now, it reminds me of a conversation I had with another person in Lavumisa, a government official who, one day, during an everyday chat, suddenly began telling me about all the bribery and corruption, venting to me about how awful it was. I listened as closely as I could. Later I asked a Peace Corps staff member about it, a local Swazi. He explained to me that the woman most likely did not expect me to do anything in particular, and that she probably talked to me out of a desperate hope that someone, somewhere, might be able to help.

As part of my Integration Report, I wrote up most of these events for Peace Corps personnel. I didn’t know if I would get Samkeliso in trouble by telling them about the secret report he’d showed me, but I thought I should mention it, so I quarantined that bit in an appendix, which I then festooned with big text warnings about keeping it secret. Later, one of the Swazi staff at Peace Corps told me I’d done such a good job on my report that she wanted to show it at a Peace Corps conference, as an example of positive community integration. She asked my permission to share the report, and after a moment of deliberation, I said yes. I don’t know if the report was ever seen outside Peace Corps, but I hope it never got anyone in trouble.

—

To be continued

—

—

Update 2/13/2025: I added “Part 1” to the title of this post to make it clearer that I originally planned this to be a multi-part series. (I already included the text “To be continued” in the original, but I guess it wasn’t obvious enough. So now I’m adding Part 1 as well.) I originally only planned to write one follow-up to this post, but this post has totally blown up already, and it’s only been a few days. So… who knows?

Update 6/28/13: I am still planning to write a follow-up for this. Here’s why I haven’t yet. For one thing, I’ve been busy, but also, this post blew up in an exhausting way. People who read my stuff regularly will already know that I get, uh, intense feedback sometimes, and it comes from both right and left; in this case, a small subsection of the far right found this post and dogpiled me on Twitter. (You can scroll down on my original Twitter thread to see some of their, uh, intense feedback, although some of the comments calling me a whore have probably been deleted by now.) I wanted to answer the questions that were asked in good faith, particularly factual questions, so I did read everything, and I answered some people, like in this conversation about reasons the HIV rate is so high in eSwatini. But the nature of social platforms is such that it’s difficult to separate the comments that try to be as mean as possible, from the comments where people are asking genuine questions.

It’s exhausting to deal with a firehose of political hatred, so after I answered a bunch of questions, I decided to take some time and work on other stuff before I write the follow-up. With that said, I have a bunch of notes for my follow-up, and I plan to finish it sometime this year.

Those who have tracked my writing for over a decade (are any of you reading this?) might recall that I did, in fact, publish some writing from Africa. But for the most part, when I was writing from Africa, I confined myself to commentary about American culture and other American stuff that I read about at a distance. With that said, there were four columns specifically about Africa that I published pseudonymously at a now-defunct website called CarnalNation. However, most of the post you’re about to read has never been published anywhere.

When I served in Peace Corps, this country was called Swaziland. It has since been renamed eSwatini. I apologize in advance if I make mistakes in trying to refer to this country, since the name changed after I left. I welcome linguistic corrections if they’re needed.

I heard recently that this has changed. That surprises me, because the notion that you ought to be willing to go where they tell you to go seemed so important to Peace Corps when I applied.

Sometimes Peace Corps Volunteers get sent home for misconduct, but that doesn’t count as an ET. And some programs get fully evacuated during emergencies, like if a war breaks out in the host country, but that is not an ET either. (Some Volunteers choose to stay behind during evacuations, but Peace Corps obviously advises against this; when I was in training, we did a scenario exercise where we had to consider how we’d persuade another Volunteer to evacuate if they wanted to stay behind in an emergency.)

Fun fact: It is against Peace Corps policy for anyone who has previously served in the CIA to serve in Peace Corps, or at least, it was when I was there. The intention of this rule is to prevent the Peace Corps from being weaponized.

Realistically, gender and sexuality affect almost everything in international development. And also everything related to culture. One book I read during that time was Susan Okin’s 1999 anthology, Is Multiculturalism Bad For Women?

Those familiar with HIV treatment may be thinking that anti-retroviral therapy (ART) can protect against transmission of HIV. This is true, and ART was being scaled across eSwatini while I was there, due to the tireless efforts of Doctors Without Borders and other groups. However, when this story was published, I don’t recall anyone in the media pointing out that ART could have protected the woman. My sense at the time was that the story was widely perceived as simply posing the question of whether she had a right to refuse sex from her husband, assuming she could get HIV by having sex with him.

I heard occasional stories about some of the king’s wives trying to escape, too, though I’m sure many of them are happy where they are. I also heard that the Swazi secret service was allegedly dispatched to retrieve those women.

This reddit post has a photo of the billboard that matches my recollection.

A multitude of complex points might be made here, about why HIV is generally so prevalent in some populations but not others, about the many ways it was theorized that the local culture contributed to the spread, and even about how the disease was interpreted within the traditional religion. If anyone wants to talk about this in the comments, I am more than happy to discuss and/or answer questions.

A rumor I once heard, but have not confirmed, is that Peace Corps Mauritania is considered one of the hardest Peace Corps posts because there is still quite a bit of slavery in Mauritania. Apparently, Americans have a hard time coping with that environment, which makes sense.

The vast majority of the blogs I used to read about sex, gender, and feminism have now vanished. I recommend Elizabeth Pisani’s excellent book The Wisdom of Whores if you’re interested in actual true facts about (a) the international HIV/AIDS establishment and (b) sex worker programs in particular. Her book was published in 2008, so it’s probably behind the times, though it was very current when I was in the field. If you’re really interested, another good book is Letting Them Die: Why HIV/AIDS Prevention Programmes Fail, written by Catherine Campbell and published in 2003.

Years later, I met Ka-Ping Yee and I interviewed him for the first issue of my magazine about his work supporting Doctors Without Borders in the Ebola epidemic. I still occasionally think about something Ping said during that interview: “For every Ebola epidemic, an entire sub-economy springs into existence. When outside nations pour hundreds of millions of dollars into an economy like the Congo, it distorts everyone’s incentives. The magnitude of the strangeness isn't clear to us from the outside.”

Chacos has a 50% discount available to Peace Corps Volunteers. I am still a customer of theirs today, though I don’t still take the discount. I have not encountered a better pair of sandals for, say, walking eleven miles on a 120 degree day.

I served in Liberia 2018-2019. I was a teacher. I saw and heard a lot of awful things but the HIV murder story you told shocked me.

I was a teacher.

For a while I had a rule in the classroom that anybody in class had to be working. One day I saw a pregnant 14-year old girl sleeping on the bench. She looked so exhausted. I didn't have the heart to wake her up. After that the rule was that you can't disturb the class.

Often students would come to class without a pencil or the money to buy one.

The students often hadn't eaten anything all day.

I saw the same pattern of NGOs throwing out money without understanding the situation on the ground.

I could tell a hundred details and stories like this but you captured the essence of it pretty well.

This has given me a lot to think about. Because of the obvious political implications of the story, I think it's important to point out that even if a lot of the efforts at changing peoples' behaviours failed, widespread ART has meant that the life expectancy in eSwatini has risen by 13 years since your time there. Maybe it's fine if DOGE cuts the equivalent of the half-built useless carwash, but they also cut PEPFAR and that will kill large numbers of people and far outweigh all benefit from everything else they do.