I recently told a story to a friend and Substack subscriber, and he encouraged me to make it my next post, so here you go. (If you’re a reader with strong opinions about what I should write on Substack, let me know! I’m open to suggestions!)

This post is about social networks, and the media, and society, and the current state of things. It starts with a hurricane.

You may have heard about a particularly devastating hurricane that wrecked Asheville, North Carolina, and nearby areas last year. It was called Hurricane Helene. I have friends in Asheville, so I saw both the national reports, and also my friends’ personal reports on social media.

Soon after Hurricane Helene hit Asheville, an acquaintance posted on Facebook that the survivors needed “research help.” I saw her post and offered to help out, as long as it was research I could do on my phone while watching my toddler. She told me there had been an unidentified major chemical spill during the hurricane. This, among other things, tainted the water. In some places, when survivors tried to drink water, including water from faucets in their kitchens, the water burned their mouths. When they waded through mud to rescue friends and family, the mud burned their skin.

This posed several immediate problems. For example, survivors had to source hazmat suits to wear while wading through the mud; by the time I got involved, that was covered. Meanwhile, they were not sure what to do about the water in their faucets. For example, maybe there was a way to purify it, so that people could drink tap water without fear? This was the sort of question she asked me to research.

As I learned long ago during my Peace Corps service, most normal hazards in a water supply can be handled by boiling the water, or alternatively, by putting small amounts of bleach or iodine in it.1 An industrial chemical hazard is different, though, and as I started researching the problem, I learned that an unknown industrial chemical hazard is much worse. The Asheville survivors thought maybe the problem chemical came from a plastics plant wrecked by the hurricane, but they weren’t sure. This meant it could have been one of, like, four thousand chemicals. It turns out that if you know what you’re testing for, it’s not too hard to test water for a chemical, but if you don’t know what you’re testing for, it’s much harder and more expensive.

Without knowing the exact nature of the chemical(s), it was unwise to boil the water, since boiling could concentrate or activate the unknown chemical(s); it was also unwise to purify the water with bleach or iodine, since the bleach or iodine might mix unhelpfully with the unknown chemical(s). Distillation would most likely work, but most of the Asheville survivors didn’t have the equipment, not to mention the time, for distillation.

Asheville was an absolute disaster area, wreckage everywhere. Federal agencies and rescue workers were going in and out where they could, but many roads were blocked. Residents were dealing with urgent, terrifying problems like rescuing trapped family members. They needed to know, immediately, whether and how to use their water, and they needed the information to be presented as clearly as possible.

Rescue workers were reportedly bringing shipments of bottled water. The simplest thing to recommend was for Asheville residents to use only bottled water to do anything important — drinking, washing food, bathing — at least until the chemical tests could be performed. When would that be? It was impossible to tell. Was there enough bottled water? Someone told me a lot was brought in, but of course, people had to transport it to their homes and so on, so I had no way to know how much most people had at home. Nevertheless, I recommended using only bottled water for everything important.

This also raised new questions, like: Were fruits and vegetables grown with local water safe to eat? I looked into that question too. It turned out that the local foods were fine in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, but they would stop being fine soon afterwards; the foods are on a “grow cycle,” and the previous grow cycle had used untainted water, but the next cycle was anyone’s guess. I passed on this information, too. Did people keep track of it when evaluating locally grown food during the next grow cycle? I imagine they were extremely busy and overwhelmed, and I have no idea if they remembered, or if they had the energy to care, if they did.

After spending a day or two researching these questions, I did my best to usefully organize what I’d learned, and sent it to my acquaintance in Asheville. They co-created a shared document that got passed around their community for a while (the document seemed largely correct at the time I reviewed it). As part of my research process I wrote a Facebook post, where I recruited help from my friends with relevant expertise, and then, when I was done researching, I updated the post with what I learned.

I tried to make my words as clear as I could while still being accurate, but it was hard because the questions have complicated answers. I had no good way to follow up to find out whether people got the right information at the right time, based on the research I did. I hope it was helpful.

Later, the chemical spill was mentioned in a Guardian piece about rebuilding after the hurricane. The author, Chris Smith, runs a food and farming nonprofit in North Carolina; he talked about how the soil would need remediation after the cleanup. Here are some quotes:

The Barnardsville farmer Michael Rayburn is also the urban agriculture extension agent for Buncombe county, which experienced the most Helene-related fatalities of any North Carolina county. He lost his ginger crop… It’s a colossal task, cleaning a mud-flattened, toxic town center. How do farmers “clean” our fields? How does chemical-soaked soil grow anything again, let alone food?

“Everywhere is going to be different,” said Rayburn. “But remember, flooding is a natural process, so it’s not the end of the road.” Soil and water testing is going to be an important tool to establish what specific contaminants farmers will need to deal with (and how to protect themselves).

Plants themselves hold many of the solutions…. Simple exposure to sunlight and the weather can be enough to break down or dilute many dangerous pathogens. The same is true of some chemicals like pesticides and herbicides. [The recommendation is to plant] Cover crops, [which] include a wide range of grasses, legumes and brassica (a family of plants that includes radishes, mustard and many others). Their roots encourage the return of life within the soil, much like taking a probiotic after a course of antibiotics.

Other toxins like heavy metals will not break down over time. For these, soil testing and targeted remediation efforts will be critical. Again, plants can help. Phytoremediation is the process of planting crops like sunflower and mustard, which can pull arsenic, lead and cadmium from the soil and into their leaves. When the plants are removed, so are the toxins. Similarly, mycoremediation uses mushrooms to break down complex carbons like oil and diesel. This natural technology has been applied at various scales from contaminated soils in community gardens to large oil spills in the Amazon.

The article ends on this note:

Sass Ayres, farm manager of Mystic Roots Farm in Fairview, North Carolina, wrote online that it’s hard to tell that their farm ever existed.

“I don’t know what’s next. Though as a farmer, I do know that everything starts with a seed. It’s the magic on which we bet our hearts & livelihoods. Once the wreckage is cleared, I have faith that there’s a seed just waiting to burst open with life. Know that we hold this hope for all of us really tight. It’s what farmers do.”

—

Around the same time as the Asheville hurricane, I saw a post go by on Twitter/X. The post author, Hannah Riley Fernandez, wrote: “there are lots of people in Atlanta under a boil water advisory after a water main break. they can’t go outside to buy water because of the chlorine gas in the air from a chemical plant explosion. some won’t hear any of this news because they still have no power from the storm.”

The terrible intersections of crises within these stories reminded me of the Asheville situation, and both remind me of a day in 2020, in Berkeley, when I woke up and the sky through my bedroom window was orange-red. I looked at the time and it was almost noon, much later than I usually slept. I had slept late because it was so dark I thought it was still night.

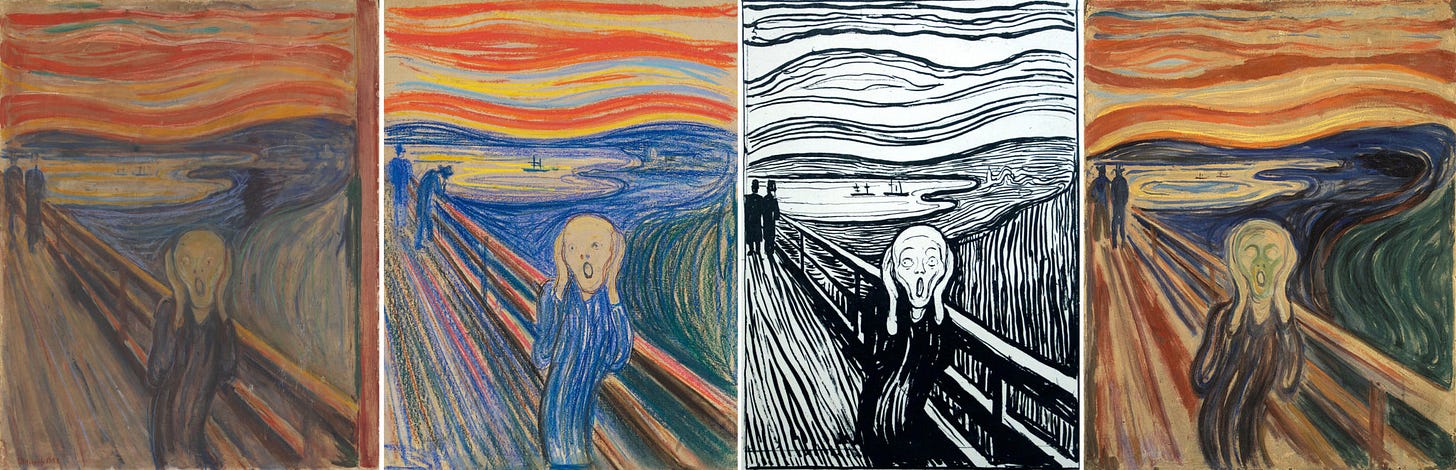

The sky had turned this apocalyptic shade due to smoke from nearby wildfires. The LA Times published a piece suggesting that the skies were similar when Edvard Munch painted “The Scream” due to the eruption of Krakatoa. “Munch is said to have sensed an ‘infinite scream passing through nature’ when he created his famous painting,” wrote the reporter Paul Duginski.

Okay, I thought when I woke up that day, it could be worse. After all, we in the Bay Area had learned to deal with this scenario. The air outside had an Air Quality Index (AQI) over 200, but that was a known problem, as it had become a yearly phenomenon so severe that people had started scheduling vacations around it, calling it “wildfire season.” A couple years before, I’d tried to tough it out and breathe the stuff without protection, and I’d learned that this was an incredibly bad idea; you’ll feel fine for a while, right up until you feel like a crazy person and your throat is on fire.

So now I had a routine for this situation. I knew what sources to check, regularly, so I had reliable AQI measurements at my fingertips. Throughout the home I shared, we’d agreed to put HEPA filters in every room, and I’d already pre-ordered extra filters in case they needed to be swapped out during smoke season. We wore KN95 masks every time we went outside, which we mostly didn’t that day, because the smoke also stung our eyes (on clearer days we sometimes did). Anyway, this year, 2020, was the first year of the covid pandemic, so we weren’t leaving the house much. In fact, we often wore the masks inside, too, so as to protect from the plague.

As I sorted filter boxes and masks, I remember reflecting on how quickly all these disasters had normalized: All these things were just added tasks in my day. Many disasters are like that, right up until they maim or kill you.

—

A decade or so ago, I went to see a presentation by some academics studying social media, I forget where (Stanford or Google, maybe?). The researcher I remember most was studying Mexican moms on Twitter. These particular moms lived in cities dominated by cartel violence. They’d formed an informal Twitter subgroup, posting real-time information about where violence was hitting their cities; for example, if there was a shootout at a gas station, moms posted the station’s location, plus whatever information they could find about the shooters. They did this to keep people in their communities safe, including their own children. Many of their fellow citizens were grateful to them. The cartels, however, did not like having so much information available about where violence was happening and when and how. As a result, occasionally the moms were gruesomely murdered.

When violence erupts, the question of which information can be found where and how, and of what stories can be told about it, becomes a newly strange question. “The fog of war.”

—

I remember a chance remark by an acquaintance, years ago. We were discussing wisdom, and the pace of technology, and that what we call “social media” got started around the time I was a teenager. He said, “I guess if our society has anything resembling ‘grandmother wisdom’ for social media, then it would be someone like you, Lydia.” I was in my thirties when he said this to me, but I know what he meant.

Often, with any given hazard, the victims could have avoided it, in different circumstances. Often they don’t hear about it in time, or don’t have the right details. Often, someone lied to them about it, sometimes because that someone stood to benefit or because the someone didn’t know any better, sometimes both. Sometimes there were no preparations to make… or sometimes a person dies knowing what preparations they could have made. Sometimes they missed the cues, the warnings, or they saw them and didn’t prioritize them.

The word “polycrisis” is more and more in vogue, lately: “A complex situation where multiple, interconnected crises converge and amplify each other.”

I’ve had very few jobs working for people who I felt had a clear sense of what we are facing. One was at an amazing journalism startup, one that won awards for innovation, called News Deeply. I loved that job and I learned a lot there. A project we worked on, but never launched, was called Disasters Deeply. The idea was a kind of digital skeleton hub to be used in disasters, a software and media package to quickly create a central place for news that people need when a disaster has just hit their community: News like “The water isn’t safe, so here’s how you can get safe water, or make your water safer at home.”

Our work was widely lauded, cited in Congressional testimony, even, but it wasn’t enough. After noble service, the creators of News Deeply eventually had to lay down their keyboards. Many such cases, in the froth of startupland.

—

In the coming decades I suspect we will see more and more things like the chemical spill from Hurricane Helene, at a faster and faster pace, often unprecedented, certainly unpredictable. These will combine with plague and with war.

Survival, for many, will turn on the ability to coordinate.

It’s not just coordination tools that will help us, of course. Survival is about many things. Tools matter, but mindset matters too, and the strength of our relationships.

I have skills with media that few people do. Yet so many things have turned out to be harder than I expected them to be, both spiritually and practically, and I’ve seen this happen to so many others in the field. I think sometimes about a post about the media that I saw several years ago by Charles Eisenstein, which he called “To Reason With A Madman.” He wrote:

Recently as a writer I have had the feeling of trying to reason a madman out of his madness…. I don’t mean to uphold myself as the one sane individual in a world gone mad (thereby demonstrating my own insanity), but rather to speak to a sense I’m sure many readers share: that the world has gone crazy. That our society has spun off into unreality, lost itself in an illusion. Hope as we might to assign the madness to a small and deplorable subset of society, it is in fact a general condition.

As a society, we are asked to accept the unacceptable…. On some level, we are all aware that it is crazy to proceed with life as if all this were not happening.

Eisenstein expressed near-despair. “I must confess to weariness,” he wrote. Then:

A key theme of my work has been to invoke causal principles other than force: Morphogenesis, synchronicity, the ceremony, the prayer, the story, the seed.

The seed.

I believe that what our society needs is a kind of soil remediation, not just literally, as in the areas struck by Helene, but on a social and spiritual level, if we are to survive. How would such a thing happen and be transmitted? What is the “soil,” what are the poison-removing “plants,” what are the “seeds”?

One might suggest: Myths, stories, ideas, frameworks. The right fact at the right time. The mechanisms by which these things spread. The inspirations that spread them.

I must confess to weariness. I pray often for guidance about what to do, where to put my energy, how to use my skills. Our media environment is not in a state that reasoned arguments can address, and I fear how much worse things will get, gradually then suddenly. What I believe needs building cannot easily be described in a slide deck I can show VCs and philanthropists, though I tried making one, at one point, and might again; but I also feel uncertain their money is the right mechanism.

Right now I’m a writer and a convener more than anything else. I’ll hope, for a while, to spread seeds here.

In fact, during my Peace Corps service, it was categorized as unacceptable “high risk behavior” if we didn’t do one of those three things to our water before drinking it — i.e., if we got caught failing to purify our water, PC admin threatened to send us home.

Appreciated the Eisenstein quote, this approach seems wise, to "invoke causal principles other than force"

Very well written.

A polycrisis is what you see when highly organized systems start to break down. It's evening in America, or at least late afternoon. Good to leave seeds for what comes after.